Stella Bruzzi once said, “Clothes are not mere accessories, but are key elements in the construction of cinematic identities”.

Identity, a term that carries a world in itself. A cinematic identity carries the burden of these worlds. In all honesty, the process of watching a film is one of finding yourself in each character. To find a glimpse of oneself, meaning of the emotions expressed, and a scuffle to reach self-awareness through the characters. A cinematic identity bears our burden of setting out to recreate our own identity, detached from the worldview of others and in the intimacy of thyself.

This identity is deciphered and manifested in the apparels of the characters. It is the attire they wear that becomes symbolic of who they are supposed to be, and how they are supposed to make us feel.

The bad news for those lost in the reveries of the filmic characters is that most cinematic symbols are highly fabricated. They are a product of popular and accepted culture. In their intention to induce serotonin, imagery of perfection is endorsed through celebrity culture and gleams of fictitious lives play havoc with impressionable minds.

They represent what is easily digestible and relatable to the audience, thus convoluting our vision of self further. There is a reason why the apparels are called costumes.

Yet, there is good news. Some of these cinematic pieces of art use clothes as a character itself. These clothes play catastrophe with our minds, changing our vision as how it all is supposed to be. It shocks us to see a non-stereotypical representation of characters and their personas. The apparel runs chaos to bring balance to our lost objectivity. But, why is it so important to encourage brave film makers? Why is it significant that purify represents the identity of all presumptions, though apparels?

Stuart Hall, one of the pioneer Cultural Studies scholars once said something about the position of enunciation. By which he meant that it is impossible to remain objective for an individual. This lack of objectivity is worn and adorned. We utter our position through our clothes and rely on clothes to make these utterances about others.

This is the truth of the audience. Then, comes the truth of the maker. The practices of representation always speak of the perspectives of who and whom it represents. The convolution begins when this identity is presented in the restriction of a culture. An identity is never static but is a living breathing organism, changing in itself, sometimes due to the miles taken or by staying put in the ever-evolving regions.

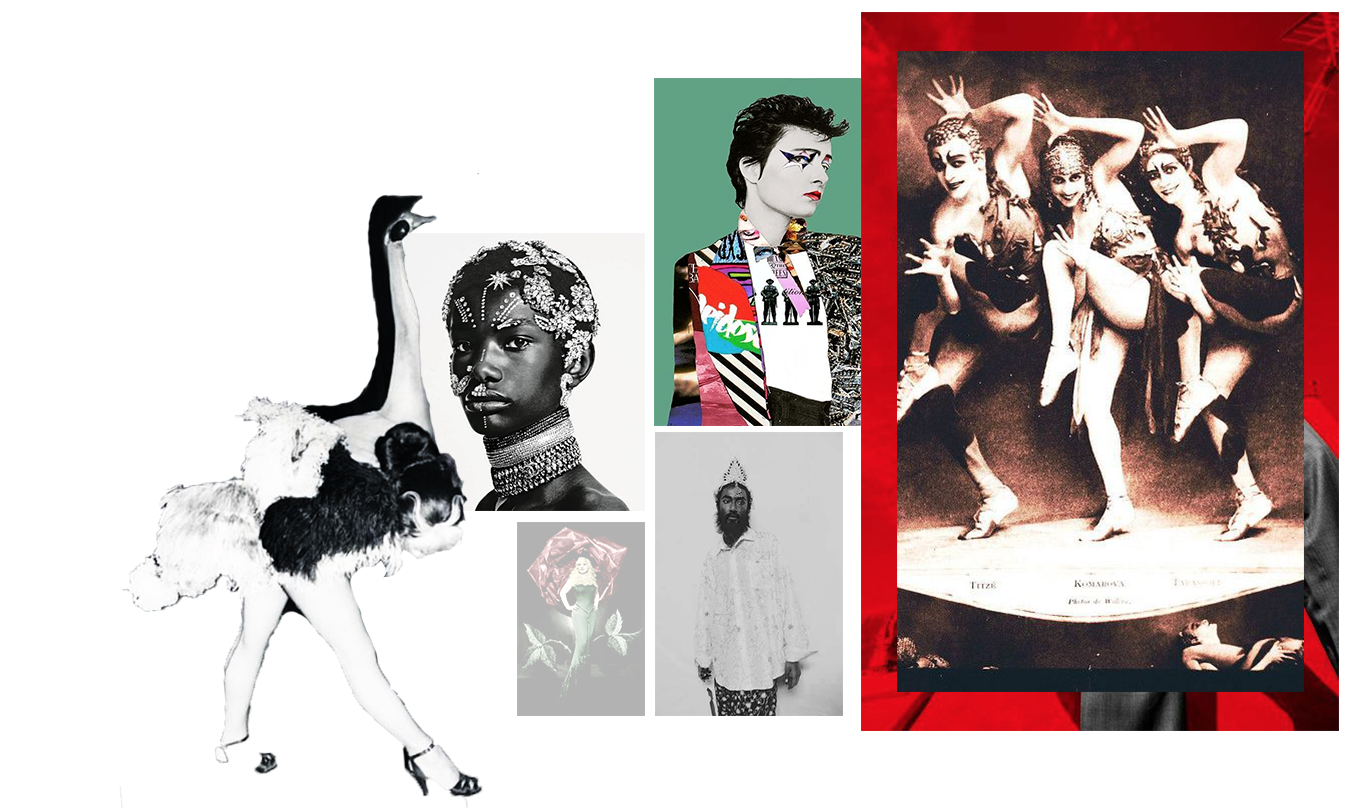

An apparel speaks of these connections between perceptions and cinematic nation. It dramatizes responding to questions asked by a community. It often serves as an escape and transcends into a world beyond. Once put-on display, an attire transports us to a post-apocalyptic world or takes centuries back to a historical time of clinches of Greek skirts. Each time sensing our immersion, enormous worlds are created in those mere apparels. The vision of apocalyptic clothes tells us much about our vision for the future of mankind. Our grandeurs about history state much about our longing for the world lost forever.

Apparels acquire the power to instigate a dialectical push and pull of this desire to escape and return to the contested body. We reimagine the adorns to make a battleground of contestation. The nuances deciphered through the dress leads us from political assessment and historiographical metafiction.

An example of such exploration through film is the story of how Bloody Phanek came into being. A young Manipuri director Sonia Nepram, reused the cinematic platform to state her personal and political rights. A political film about a piece of cloth became ever more personal.

Tied to the waist like a sarong, falling neatly on the ankle is the phanek, a traditional formal loincloth worn by many women, in the north-eastern state of Manipur, especially by the Meitei tribe. Women wearing phanek protested against the British imperialists in 1904 and 1939, against injustice and unfair orders, repeatedly mentioned through the film. The statues symbolising the fight have been built in Imphal, the capital city.

A common belief suggests that an agitated woman can thrash a man with phanek, and it shall bring her misfortune, and even death to the man in question. The director realised the discourse of gender bias in phanek which once was a symbol of protest.

It is not just a cloth but an assertion of oneself. The cloth becomes the voice of the women in the film and for the director in the socio-political platform. With its traditional embroidery which constitutes numerous historical markings, a phanek is powerful, and considered sacred by the people of Manipur. It is an artifact of history to be written.

“Our grandmothers used to tell us that thrashing a man with a phanek was no different from challenging his masculinity,” says the director.

A fabric is able to colour us into political rage, it becomes a symbol of hatred as easily as it attains the power to change our perspective about the world we visualize. Fabric gives space for exploration and discovery in the cinematic world. It gives space to contest abrogation long dragged in our communities. But most importantly, it can start a discourse.

0 Comments